“She was 10 when her mom died.”

“She was 10 when her mom died.”

“No. She was 12.”

“Are you sure? I thought she was 10?”

“Hold on,” the funeral director said, “I can pull up her mom’s headstone with a program we have here…Let’s see…Here it is: Laura Elizabeth Willis died August 18, 1958.”

“So you were right, she was 12 when her mom died.”

I put my head down flat on the piece of paper I had scribbled “ROF 6-8,” in a handwriting that didn’t even look like my own. Writing “Receiving of Friends” felt like too much effort. My arm felt like concrete. The air was cold and stale and everything seemed way too clean. It didn’t seem like real life; to think that only a few floors beneath me were bodies in various stages of preparation, while here in this room, a far too chipper coordinator asked us if we wanted her to “grab some K Cups.” “Are you okay?” my mom asked. “I mean, as okay as I can be I guess,” I told her.

Just 29 hours before my Nana had died suddenly.

No warning. No fanfare. A massive internal bleed, intestinal blockage, heart failure, seizure, three failed attempts to bring her back and then gone. Here we were — “her girls” — my mom, aunt and me, planning her funeral and cyber stalking cemeteries for her long dead relatives.

Later, at the ever-dreaded “ROF” Nana’s best friend told me that even though I was her granddaughter, she always regarded me as her youngest girl. Right before they closed the casket, there we were, my mom, aunt, and I. The girls. Nana’s girls. Standing there together looking at the body of the woman we lost.

I read an article once; something about “who was your mom before she was your mom.” Many of the daughters posting the photos for the spread were amazed to find out that their moms were hippies, or career women, or any other variation of personage different than just plain ole “mom.” Although my heart is shattered still nearly three weeks later, I’m comforted in really knowing who Nana was. There was nothing anyone could have told me or that I could have uncovered about her that would shock me, unlike the women in the article.

The memories I have of her and the stories I grew up hearing from her or about her have sustained me during this time.

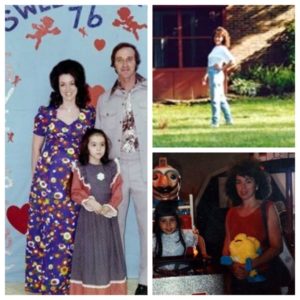

Before she was Nana, she was Shirley Ann Williams. The oldest daughter of Laura Elizabeth and of a biological father who ran out on them. (Years later, a relative of her dad’s would come to the door with news that he was ill. “He wants to see you, he’s about to die.” “Good,” Nana said and closed the door in her face.) Two sisters and a brother soon joined Nana, but when her mom died at the age of 32 from cancer, the siblings were split apart; Nana stayed on a farm in Mascot with her grandparents. It was there, at the age of 15, while sweeping the front porch with rollers in her hair and wearing her Carter High gym uniform, Shirley Ann Williams met 19 year old Jack Arnold Payne. Jack said she was the most beautiful girl he had ever seen and convinced her to run away and marry him. At 16, Shirley Ann Williams became Shirley Ann Payne in a courthouse in North Carolina, with a fake ID.

(Years later, at their 50-year anniversary party, we joked that they weren’t actually married — because fake ID — and that they had spent the last 50 years “living in sin.” We found this way more hilarious than she did.)

Over the course of her lifetime, there would be a year spent alone with my infant mother in Myrtle Beach where my Pap had to travel to find work as an electrician. A small house with a pink kitchen, and finally her dream house in which she lived until she died.

There would be bad times and good times. Times when my Pap was a less than desirable husband, to be minimal in his transgressions. There was the time she told him, after years of silence regarding his behavior, that he could change or she would kill him. This resulted in him finding religion and repairing their marriage, maybe out of genuine desire to do so, or maybe out of sheer shock.

She was a mother at 17, again in her early 20s and a grandmother at 40. A great grandmother at 64.

She taught Sunday School and VBS. She helped coach softball. She snuck through the fence behind a local florist (who was also a good friend and next door neighbor) to avoid paying admission into the fair one year.

There was a trip to Charleston with my mom, my aunt, and me, where she casually said, “You know, if something ever happened to your Pap, I think I could be a lesbian.” This lead us to all nearly faint. There was the Christmas Eve when she told us all in great detail why we would want to circumcise our male sons, citing my Pap as an example of someone who wasn’t, while he casually ate ham and eggs. I could go on and on about her 71 years on Earth…

I write all this to say that one day, the stories we hear from grandparents or other elderly relatives will be the only things we have to keep us going in their absence. I promise I have not been an ideal steward in listening and remembering everything I’ve ever been told by my grandparents, but I am thankful for what I have retained over the years.

It might sometimes be boring. They might tell you the same things over and over. They might mention things in passing that you’d never register as important. Until they’re gone. Until these stories are all that you have.

“Are we doing an open or closed casket?”

“She’d want open. I mean, if we can.”

“Are you sure?”

“Yes. Any time she talked about someone having a closed casket she would do that typical southern lady thing. You know, whisper ‘well, he had a closed casket’ like it was some huge scandal. And like if she didn’t whisper it someone would hear her.”

“Haha, you’re right I forget that.”